6.13 Recommendation algorithm

Page reading time: 9 min

→ The recommendation algorithm estimates a rating that the user would give to a piece of content (book, film, music, post, etc. ). Using this rating, it recommends the content that:

- is most likely to appeal to the user;

- maximises the seller's profit.

These algorithms were born in the 90s with the rise of e-commerce.

The people in charge of choosing and designing recommendation algorithms are mainly data scientists. They suggest which algorithms to use based on:

- those they can apply from a technical point of view;

- service strategy.

Recommendation algorithms can be based on several types of elements, such as:

- collaborative recommendation (one of the most widely deployed at present and one of the most successful):For example, many users have seen the films 'Batman' and 'Superman'. When a user watches 'Batman', 'Superman' will be suggested.

- likes: the algorithm counts the number of likes to determine the most popular elements. These elements will be highlighted.

- items viewed by the user: the algorithm will recommend an item based on what the user has already watched. For example, if the user has read Harry Potter 1, it will recommend Harry Potter 2.

- images: the algorithm will use image metadata to suggest similar content.

In general, a service uses several types of algorithms in combination.

The main risks of recommendation algorithms are:

- recommendation conformism: only finding items that are similar to those that the user likes.

- propagation of racist and sexist bias: when learning is based on data that reflects stereotypes.

- emphasis on short-term user benefit: when the elements highlighted push the user towards what interests them at the moment, rather than what will help them progress. For example, highlighting fast, processed food (hamburgers, etc.) over healthy food. Algorithms are designed to make the user click.

That's why it's important to implement certain best practices, such as

Keep control on recommendation algorithms

Algorithms are created by humans, and all humans have biases. That's why it's essential to keep a hand on your recommendation algorithms, in order to compensate for certain biases present in the algorithms.

Keeping control also enables us to highlight invisible content (that doesn't stand out with the algorithms used). For example, on a streaming service, we can highlight auteur films, which are hardly visible with the algorithms, as they are rarely viewed.

Limit recommendation systems based on profiling

Profiling is the creation of an opaque, non-configurable profile for each user. Using this, services work to predict whether or not an item should appeal to the user. The aim is to maximise the time spent on the service and the number of interactions.

If we go back to the types of algorithms presented earlier, we find this profiling mainly in:

- collaborative recommendation;

- elements seen by the user.

Part of the content is invisible to the user, because according to his profile, he would be less interested in these elements. One of the main risks is being trapped in a bubble effect.

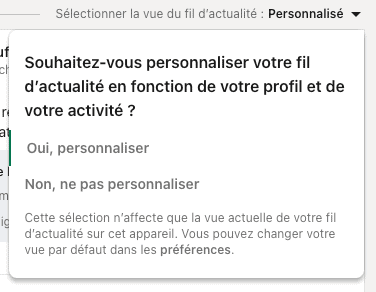

This practice is limited by article 38 of the DSA. Very large online platforms are obliged to offer at least access to content without profiling.

To comply with this legislation, LinkedIn has added (August 2023) a button to select the type of news feed view: with or without profiling.

Being transparent

Choosing the type of recommendation algorithm is a strategic choice. However, users do not know the rules of the algorithms (how the content displayed is chosen). They have no control.

This lack of control leads to the risk of being trapped in filter bubbles (mainly visible for search engines and social networks). It becomes difficult to form a critical opinion when you're rarely confronted with opposing views.

To protect users from this phenomenon, article 27 of the DSA requires:

- transparency on the main parameters used in algorithms, and why;

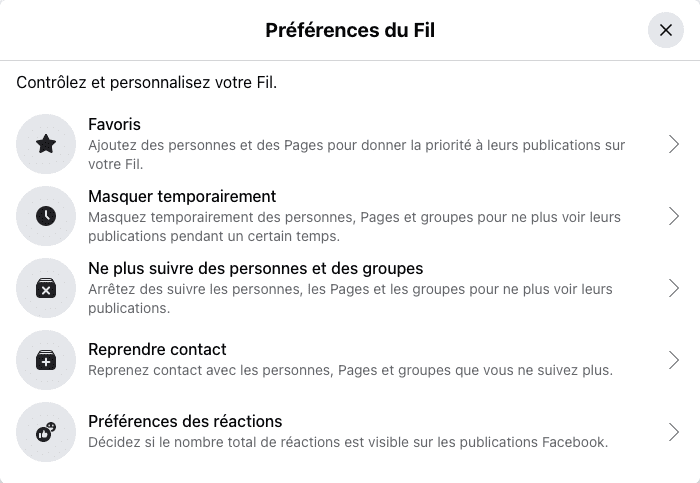

- the means to modify or influence algorithm parameters;

Best practice

To be transparent, users must be able to:

- understand the different algorithms used;

- control their profile to limit the bubble effect.

Watch out for the bubble effect

With the use of recommendation algorithms, users can find themselves trapped in filter bubbles.

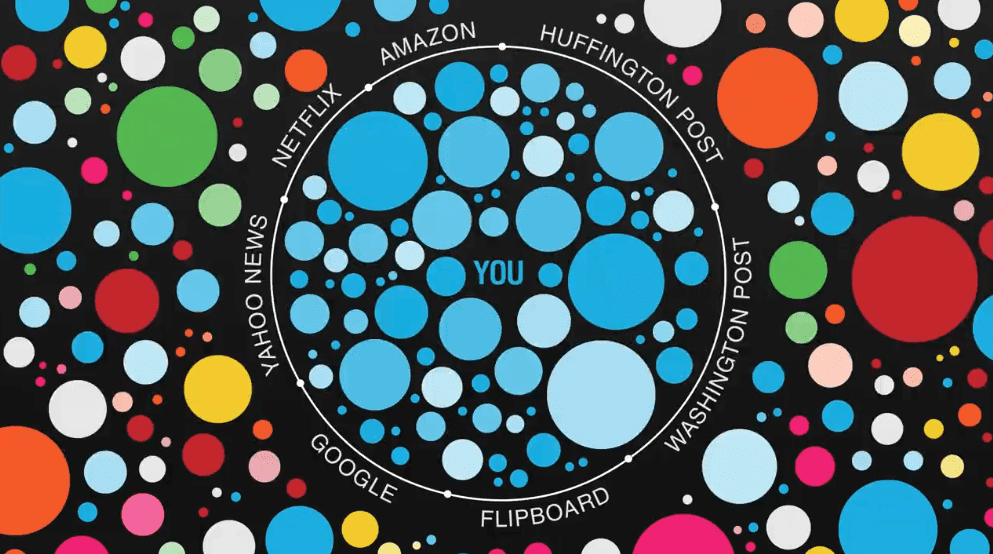

These filter bubbles exist when the user only sees information that has been configured for them, according to their tastes. The results displayed never go beyond the known categories. This maintains confirmation bias: the algorithm hides content that might challenge our beliefs. This is particularly dangerous on services like Twitter, where content can easily become extremist.

The bubble effect is also a danger, as users are likely to be unaware that they are enclosed in a bubble.

Some sites no longer exist in a generic way, but are adapted to the user. For example, there is no longer one Google, but different version of Google that change according to the user (see Eli Pariser's Ted lecture on the dangers of filter bubbles).

Source: Eli Pariser's conference on the dangers of filter bubbles, March 2011

Finally, we need to be careful to give users solutions for getting out of their bubble. The confinement this can cause is recounted in Marc-Uwe Kling's science-fiction book Quality Land.

In this universe, everyone has a user profile and only sees what has been selected for them. Spouses are chosen and products are delivered before the user even asks for them. Even the news presented is very different from one person to the next. It's when the book's hero has a problem with his profile and tries to change it that we discover just how complicated it can be to get out of these filter bubbles.

Best practices

If you're working on a service that's likely to generate filter bubbles, you should:

- be as transparent as possible about how the algorithm works;

- allow the user to set the parameters for what they see (or even reset their filters to zero);

- allow the user to step outside their bubble at times. Netflix's random button could have been a good idea, but it's not totally random and remains based on user preferences.

Find out more:

- Fake news and ideological polarisation: Filter bubbles and selective exposure on social media (English)

- Beware online 'filter bubbles' - Conférence TED (English)

- The filter Bubble: What the Internet Is Hiding from You - Eli Pariser book (English)